Push-to-web and the role of incentives

With Vera Toepoel , and people at NIDI and the German Institiute for Demographic Research we have in 2018 conducted a large experiment to tranfer the Gender and Generations Survey to a push-to-web survey. Several papers will document what we did, and what particular designs worked and did not work.These papers will come out later in 2021, and I may publish some more posts about this design. In this post I want to focus on the role of incentives in push-to-web surveys.

Incentives are commonly used in surveys nowadays. Online panels for example ‘pay’ respondents for their time. When they complete a survey they either receive ‘points’ they can redeem at a shop, while some probability-based online panels (like The LISS panel ) periodically pay for every completed questionnaire by direct debit. Incentives here serve as conditional rewards for participation to make sure that respondents participate in the study.

Incentives can also be used unconditionally. Unconditonal or pre-paid incentives are paid before someone has actually responded to a survey. The reason why unconditional incentives often are more effective in boosting response rates is that respondents may have the feeling that they need to return a favor to the organisation that sent them some money; survey participation is here seen as a social exchange .

Push-to-web surveys normally use invitation letters sent by post to invite respondents for a web survey. Incentives are here considered a key and essential element of the survey design. In uni-mode surveys (mail, face-to-face, telephone or web) incentives are often effective, but there are also ways to do surveys without incentives. But in push-to-web surveys, they are essential. Why is this?

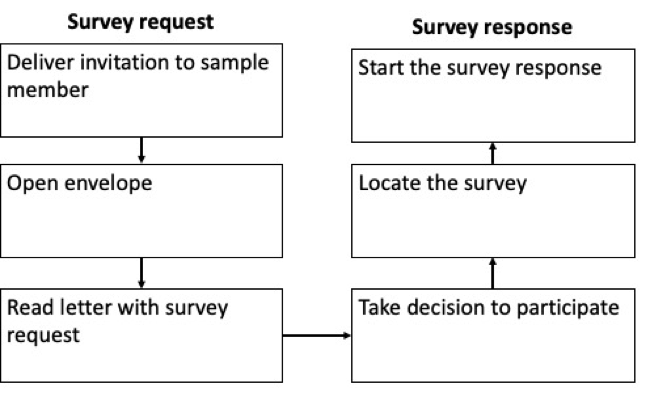

I believe that incentives are crucial, because the process from receiving the invitation letter to actually starting the survey online is complex, and includes many more steps than any uni-mode design.

1.the first challenge is making sure respondents open the invitation envelope and read the invitation letter. 2.after reading the letter, the respondent must take a decision to participate in the survey. Once the sample member has decided to participate in the survey, he or she has to 3.find a device with an Internet connection, 4.go online, 5.browse to the URL where the survey is hosted, and (often) type in individual credentials so that the survey organisation can identify the respondent.

In push-to-web surveys, unconditional incentives do not help in the first step: opening the letter. But in all of the next stages, incentives may help respondents to overcome these barriers, even when they face some troubles e.g. locating the survey.

Figure 1: The ‘customer journey’ when receiving a mail invitation for a push-to-web surveys

Figure 1: The ‘customer journey’ when receiving a mail invitation for a push-to-web surveys

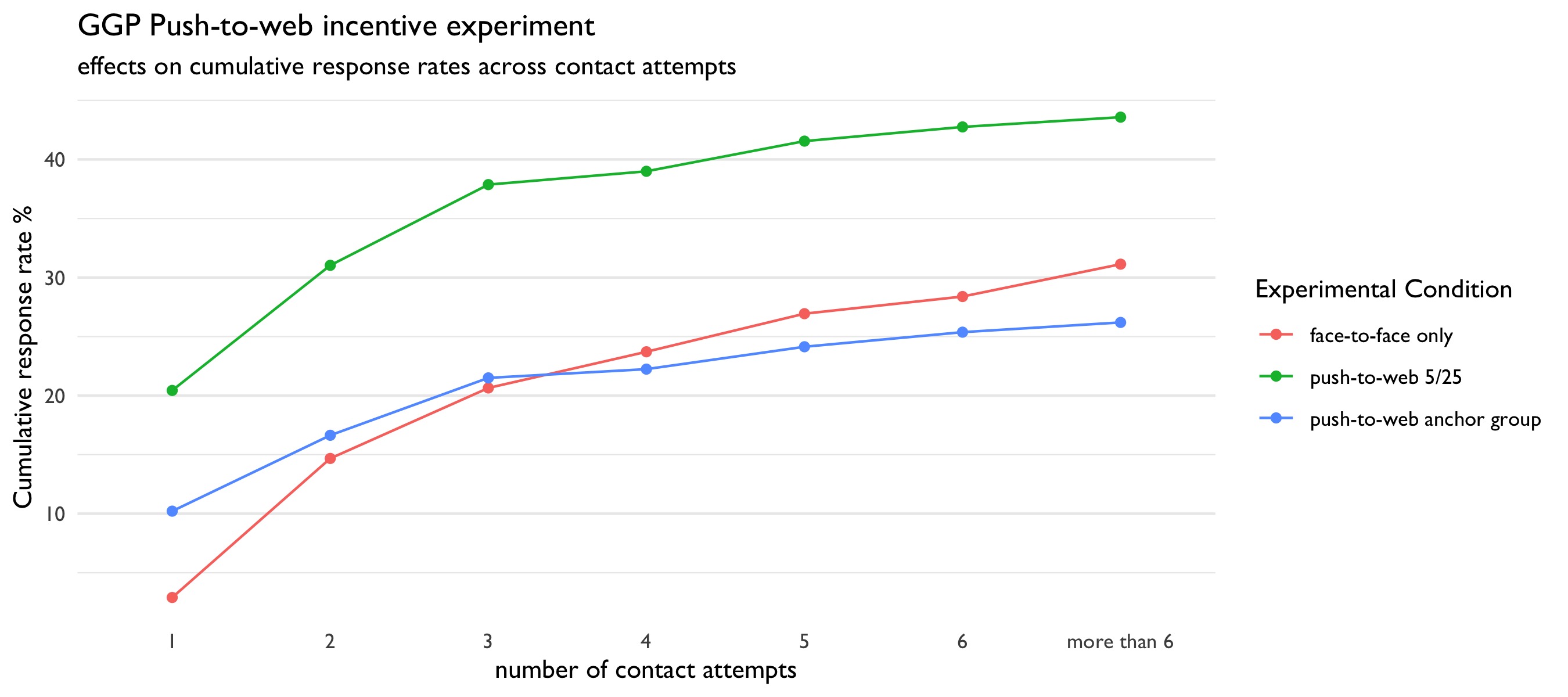

In our survey, we found that a push-to-web survey with a 5 euro unconditional incentive did almost as well or better than a face-to-face survey without incentives. Response rates in the push-to-web survey were just 3% points lower in Germany, and actually 20% points higher in Croatia. A further findings was that combining unconditional and conditional incentives works even better. Adding a 25 euro conditional incentive to the push-to-web design led to a response rate that was 18% points higher than using just the unconditional incentive. And although paying 30 euros of incentives to web respondents sounds like a lot, the survey was still more cost-effective than the face-to-face survey. For the future, I think there is much more work to do on incentive structures. How do we comunicate the incentive on the envelope containing the invitation letter to ensure the letter is opened? What levels of incentives should we use, and how to combine unconditional and conditional incentives? Until now, there is a limited body of experimental push-to-web studies. Most of these show that push-to-web surveys show great promise, and careful experimentation can surely help us to improve push-to-web designs even more.

Figure 2: Response Rates (AAPOR 4) across contact attempts

Figure 2: Response Rates (AAPOR 4) across contact attempts